the missing piece

Every time I go to the museum it’s like I’m entering a very specific world. People speak more quietly, walk around more slowly (so as not to tap their heels on the floor), and watch their every move so as not to attract the attention of the staff by approaching the sculpture too closely or leaning too close towards the canvas.

I’m in a museum, yes, but I’ll be trying to act as if I’m not there – and I know many people feel the same way, with our ultimate goal being not to disturb the sacred atmosphere that prevails there. But in doing so, we tend to forget that we, too, are part of the museum.

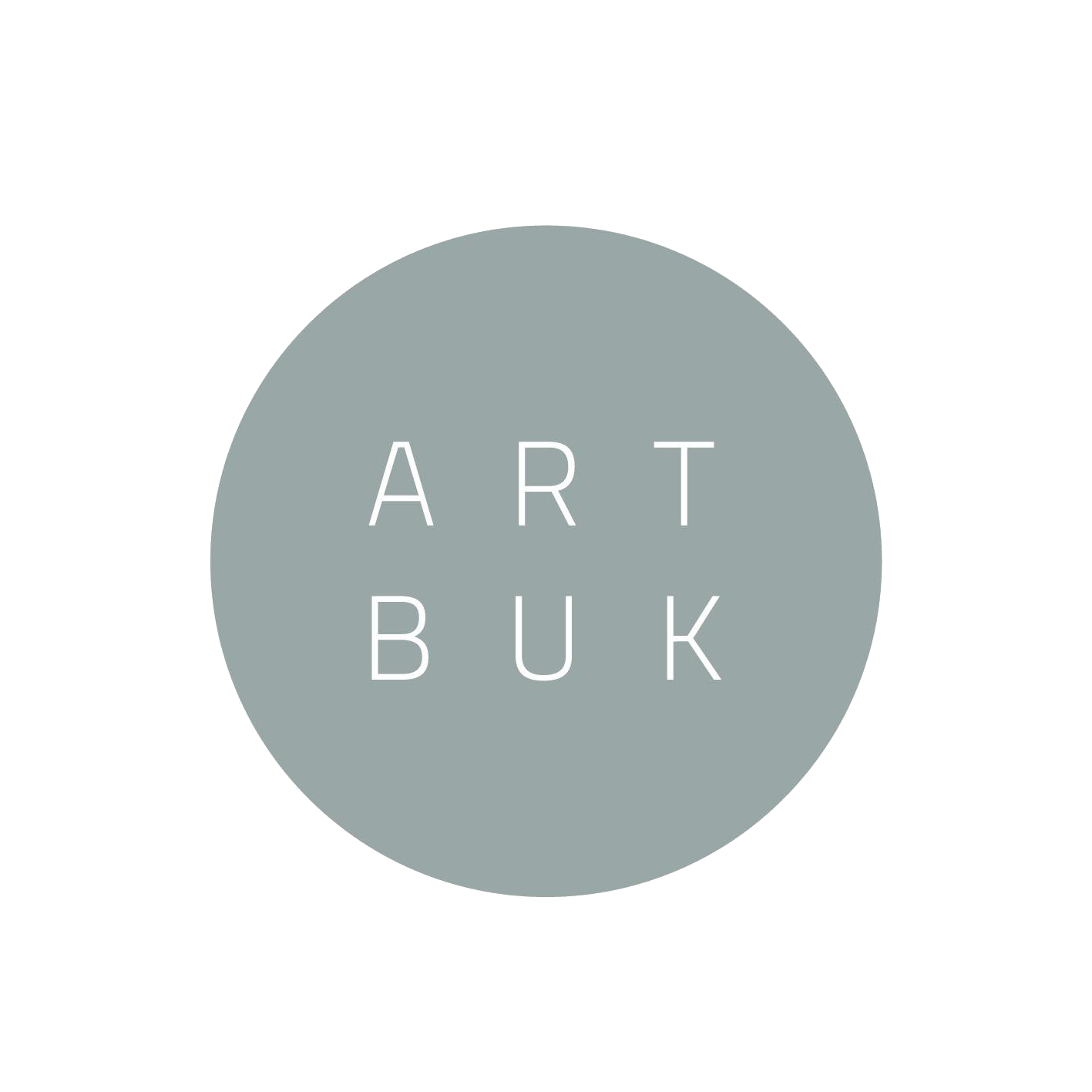

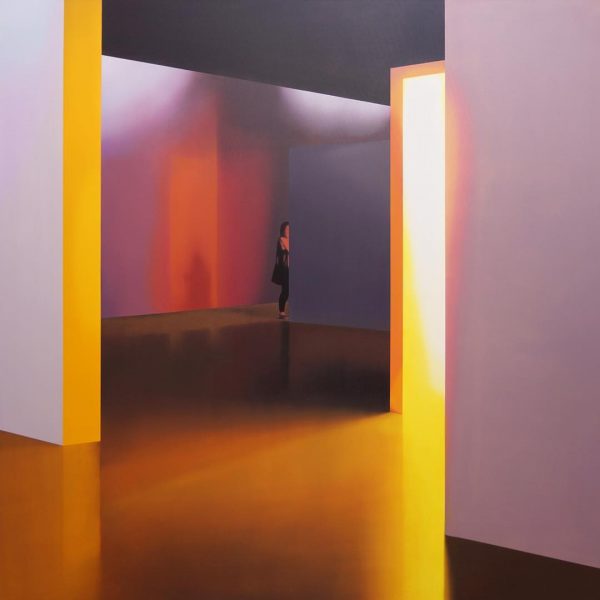

This feeling is captured by Mateusz Maliborski in whose paintings we find modern museum interiors (the so-called white cubes), only that in Maliborski’s artistic world, works of art are not exposed at all. They recede into the background or are completely removed from the exhibition space.

Instead what the artist focuses on is visitors themselves. And it is them, not exhibits, that are the subject of his paintings. The black silhouettes of men and women stand out against the background of bright or colorful empty walls, resembling a theater of shadows. One might ask what’s so interesting in such compositions, apart from nicely framed stills that may look impressive on the wall? The answer is: quite a lot, actually.

In a series of paintings exposing museum rooms, where visitors, not works of art, are in the foreground, Maliborski aptly points out that the viewer is an integral part of museum institutions and that works of art acquire their true meaning only when they are viewed. And so, knowing that the goal of art is always to interact with the viewer, we should perhaps have a little more courage next time we walk into a museum, because our presence there is pivotal!

In the works of Maliborski we can also detect elements of something that can be referred to as voyeurism (French for ‘peeping’). The artist impersonates a certain someone who, while walking around the museum, does not admire the exhibits, but stealthily watches the likely unaware visitors. And although everyone is visible in public space, such frames are a bit like peeping through the proverbial keyhole.

What is more, by interacting with the artist’s paintings, especially when we watch them in a gallery space rather than on a computer screen, we close the loop in a curious way – we are viewers looking at a painting with other people looking at another painting. Whether we like it or not, we become part of this surprising composition, as perfectly illustrated by the fact that we, the viewers, are a part of the art world to a much greater extent than we think!

Transl. Jakub Majchrzak