white city

What do Polish rap, minimalist architecture and the rise to power by Adolf Hitler have in common? It would seem that we won’t find a common denominator and the components are not only unrelated to each other, but also lie as far apart as the distance from Poland to… Israel.

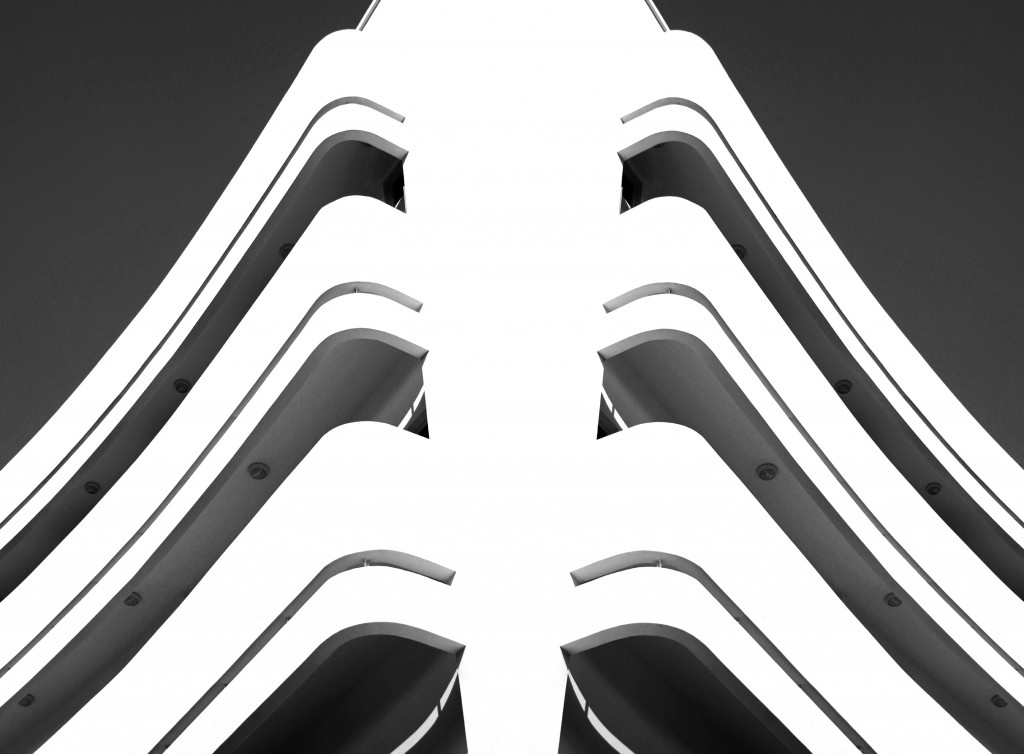

The White City may be reminiscent of a ghost town. And even though there have indeed been moments of neglect throughout its history, for almost two decades it has been slowly regaining its splendor, prestige, as well as its rightful place on the architectural pedestal.

But enough with the puzzles! It’s time to answer the question posed before, which is probably haunting many of you. Our Polish readers should recognize the hit song in which Polish hip-hop artist Quebonafide raps the following lyrics: “I miss Tokyo glowing like a neon, I miss Tel’a’viv white like a veil …”. It was in Israel’s Tel Aviv (which, incidentally, was founded at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries by the Jews tired of living in Jaffa, which was struggling with overpopulation and sanitary problems), that in the interwar period a district of minimalist white houses was built which decades later was appreciated by UNESCO as the settlement comprising a total of 4,000 sites.

When in the early 1930s the anti-Semitic mood became evident in Germany, and Adolf Hitler slowly but surely seized power, many local Jews decided to leave the country and move to Israel. Among them there were distinguished architects taught under the watchful eye of Walter Gropius – the key figure of the architectural school known as the Bauhaus. With its modern minimalist style, it focused on the needs of man as a social unit, as was necessary at the time, and in so doing it departed from historicizing trends, eclecticism and the thoroughly decorative Art Nouveau – the echoes of the pre-First World War period.

German, but also other European, architects found fertile ground upon reaching the new metropolis. Tel Aviv was supposed to be a modern and open city. For almost a decade, the district grew to include modernist houses, tenement houses, public buildings and spacious green alleys. Inspirations were drawn not only from the Bauhaus, but also from the international style touted by Le Corbusier. The buildings had a distinguishing shape, strongly cubic or with rounded corners. And by adapting European patterns to the needs of Tel Aviv’s hot climate, the designers reduced window holes and added balconies which soon became the center of evening life for the locals.

Over time, younger generations began to move to the more modern parts of the city and many of the original owners died without leaving a clear inheritance situation. And so the old icon of modernism started to depopulate, until it fell into disrepair and turned gray. Before the inevitable finale, under the wheels of bulldozers making room for glass skyscrapers, it was saved thanks to the inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2003 as the world’s largest Bahuaus settlement. Since then, the district has been restored with a view to reviving its original splendor and the specialized Bauhaus Center now offers tours following the trail of the outstanding architects and local gems.

transl. Jakub Majchrzak