first

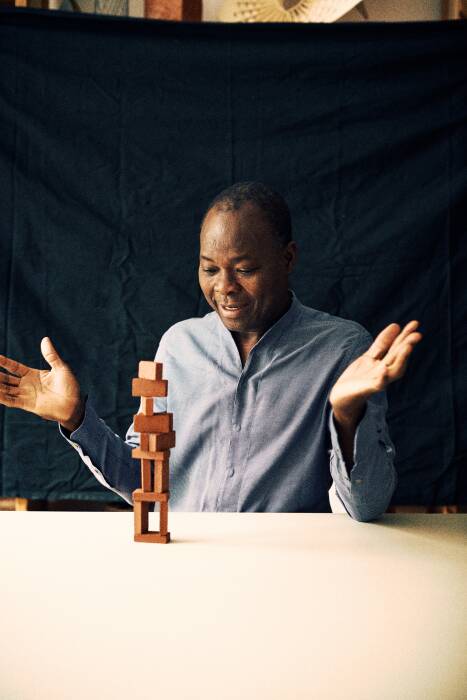

The Pritzker Prize is the Oscar of architecture and an ultimate dream of every architect. Each year, representatives of this sophisticated industry hold their breath awaiting the announcement of the laureate, who, in addition to the $100,000 cash prize, earns himself or herself a place in the pantheon of the most outstanding architects to have ever lived. This year’s jury selection, Diébédo Francis Kéré, is a unique artist in many ways and will forever go down in history as the first black and first African winner of this prestigious award.

That said, Kéré seemed to be predestined for „first” already as a child. Born in 1965 in the small village of Gando in Burkina Faso, the tribal chief’s son was the first representative of the local community to pursue formal education. And so, at the age of 7, he was sent to stay with his uncles, and years later became officially a carpenter. Having been awarded a scholarship, he was given the opportunity to do an internship in Berlin where he ended up enrolling in the faculty of architecture. Now, this is where the most important chapter of Kéré’s creative and meaningful period begins.

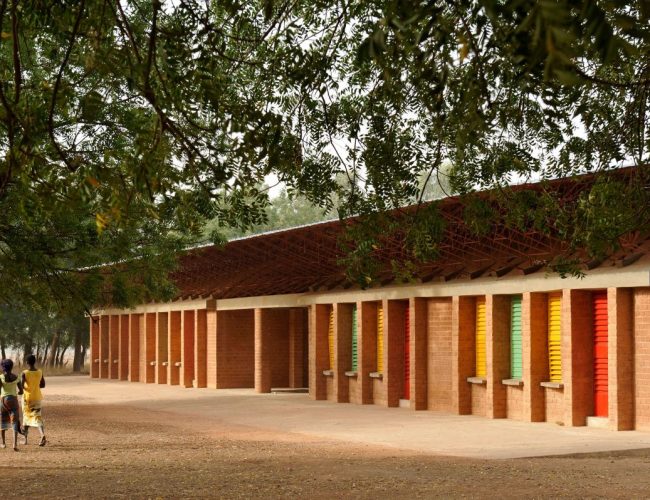

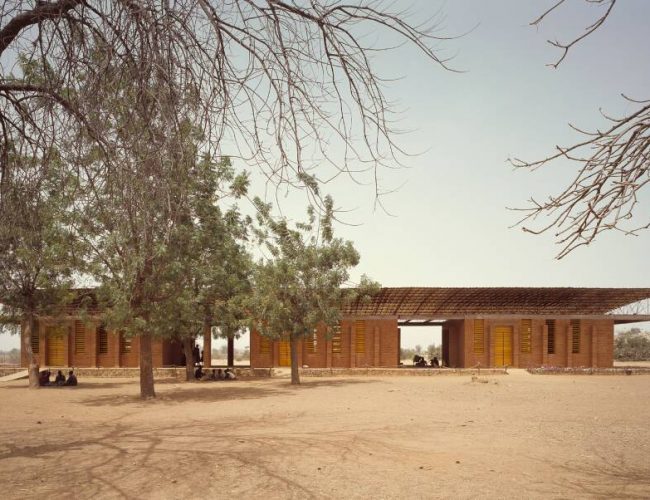

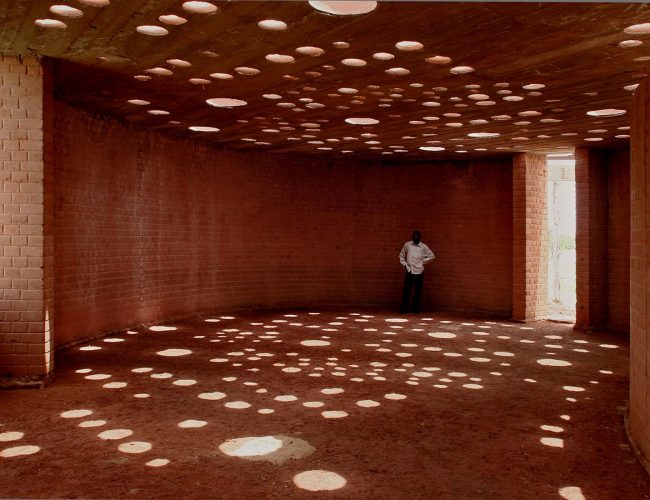

Some students write master’s theses, others create projects, and still others, like Kéré, come up with something so groundbreaking and important that even the greatest savants are swept away. A school designed for his hometown of Gando, which he designed as part of his final school project, not only caught the attention of the industry as such, but more importantly, changed the lives of the villagers it was destined for. And although the facility was built back in 2001, its positive impact can be felt to this day.

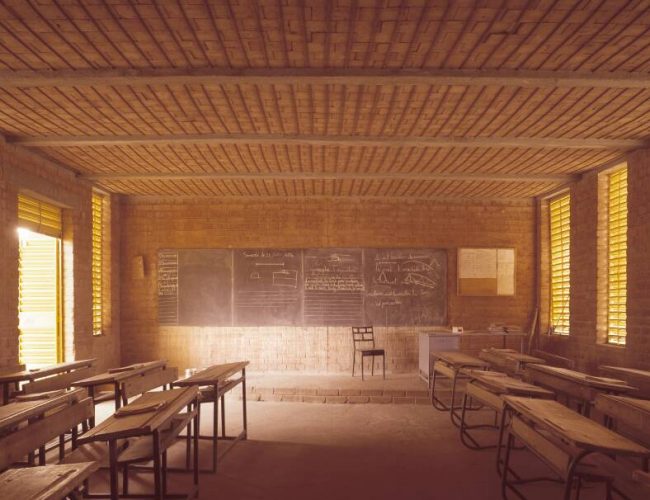

While there were more and more schools being built in the poorer areas of Burkina Faso at the time, Kéré argued they were not suited to the specific nature of the region’s needs and capacities. The problem was primarily the material they were being constructed with: concrete, which required a lot of electricity to produce and was therefore far too expensive. In addition, the concrete walls impede proper air circulation, which, at 40 degrees Celsius, significantly reduces the comfort of learning. A few hours of school inside a sauna doesn’t sound very encouraging to anyone.

Fortunately Kéré knew the local problems and needs inside out. And although he learned about the most modern solutions in Europe, he consciously gave them up in his school project. Instead, he opted for inexpensive and easily accessible materials, and involved the entire community in the project, drawing on both their knowledge and experience in the process. This is how clay blocks and eucalyptus wood were used to build the new facilities (schools, libraries and teachers’ homes), and as befits a pioneer, it was Kéré who first saw the potential of this tree in construction.

The Gando community is largely illiterate, so the architect decided to translate the technical blueprints into a familiar “language” and would present the school’s design in the form of drawings made in the sand. Francis Kéré understands that certain attitudes should be implemented from an early age, which is why students of the school were asked to bring a pebble to the construction site every day for one year, thus learning the responsibility and importance of community involvement.

Heat, lack of water, poor diet, deforestation (and therefore little shade) – these are all daily bread for small communities in Burkina Faso. The solution proposed by Kéré was brilliant in its simplicity. He initiated the creation of a mango plantation. The fruit trees have replaced previously grown eucalyptus trees, which require a lot of irrigation, and as such, absorb a lot of nutrients from the soil without being a source of food. Hen pens were then placed around the mango trees – the trees provide the necessary shade for the animals, while bird droppings are a natural, low-cost fertilizer.

Diébédo Francis Kéré proves that architecture is not only a beautiful setting, but also a tool to change the world with, equalize opportunities and combine the modern with the traditional. And isn’t it just what we need today?

transl. Jakub Majchrzak