a change of perspective

Sea coast, pristine mountains, idyllic meadows, or…factory smokestacks! Landscapes in painting can show a variety of different sceneries, from traditional representations of the beauty of nature to industrial landscapes to which there is more than meets the eye. Today, when we think of factories and large manufacturing plants, we also think of environmental pollution, global warming and different ways to be more eco-friendly. But this wasn’t quite the case at the time when many of the paintings that we’re about to see today were made.

Compositions by Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth and George Ault date to the interwar period or the years immediately following World War II. And it is precisely the context of those decades that’s essential for understanding the gist of these and other similar artworks. When the industrial boom was in its heyday, concerns such as environmental footprint or prejudice to human health were for the most part ignored. Instead, industry was seen more as a window of new possibilities: man as an individual and a society that rises from the successive wars. The emerging factories provided new jobs, and therefore means of subsistence for workers and their families, while propelling the economies of those countries where industry was prioritized.

Looking at industrial-themed canvases, we see they are dominated by tall shimmering chimneys, big production halls, water towers, and a panorama of densely packed, compact buildings that stretch across the horizon. Charles Sheeler’s paintings are known for their photorealism, owing to him having been professionally involved in industrial photography. His fascination with industrial landscapes can also be explained by the fact that he himself owned a farm in Pennsylvania. Charles Demuth had a similar approach to industrial architecture in his paintings, but with a more pronounced focus on geometrical patterns a la cubism.

Paul Kelpe, meanwhile, offers us a completely new perspective on urban landscape. For him, industrial buildings are just a pretext to show abstract places that are a product of his own imagination. Here, a complex piece of machinery does not represent a real device, but instead, is a nod and an homage to industry considered as a whole.

Among Polish painters who eagerly looked to industrial landscapes is Rafał Malczewski, son of symbolist painter Jacek Malczewski, whose compositions can tackle almost seamlessly serene Podhale landscapes on one hand and Silesian factories on the other. If anything, this shows that admiration for nature and its beauty can indeed go hand in hand with appreciation of civilization and industrial development which comes with many opportunities.

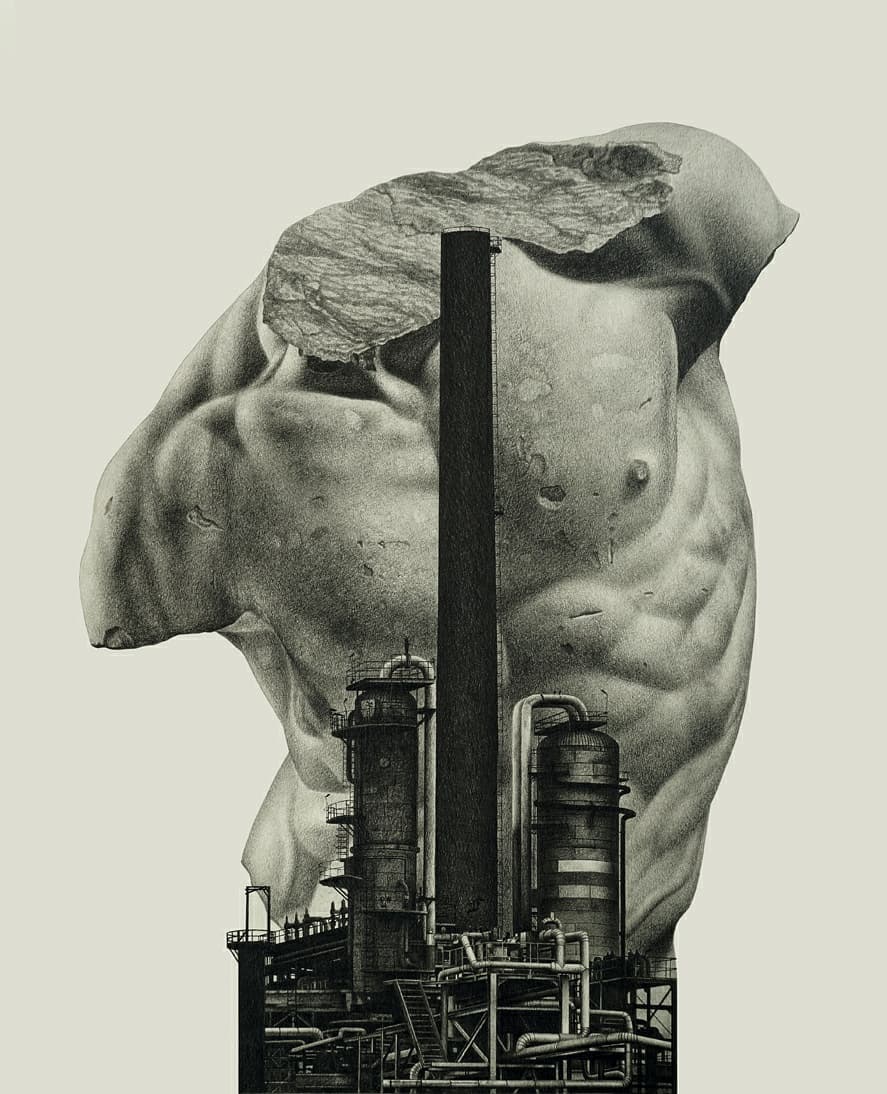

Factories easily bring to mind something very modern, but what if we wanted to set our eyes on the other end of the spectrum, say ancient Greek and Roman art? Well, it is exactly that very contrast that’s explored by Slava Fokk, who juxtaposes in a highly original way the beauty of ancient marble sculptures with the industrial urban infrastructure, revealing just how much has changed in between these two dots on the timeline of human history.

transl. Jakub Majchrzak