tea o’clock

Tea – a wildly popular drink that keeps us cosy in winter evenings with a book or Netflix, accompanies our social gatherings and is synonymous with a much-anticipated break after a long work day. Its popularity stretches across the globe: for example, in Poland, over 30,000 kilogrammes* of tea leaves are brewed annually, and in China – the world’s largest tea drinker – more than half a tonne is consumed every year. Whether you take yours black or green, leafy or in teabags, with milk or a lemon wedge, make yourself a cup to savour our subjective selection of some of the most interesting and most beautiful examples of teawares from East Asia, home of the humble camellia sinensis.

Notorious tea drinkers may be familiar with its somewhat fantastical origins. A popular legend says that nearly 4,750 years ago, a few camellia sinensis leaves fell into a cup belonging to one of China’s mythical rules, the emperor Shennong. Flabbergasted by its exceptionally refreshing taste, he subsequently established the custom of brewing and drinking tea. Historical evidence is, however, far less romantic – the earliest records show that tea was consumed primarily for medicinal purposes during the Han dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). A more comprehensive textual source on tea is found later in the Tang dynasty (618-906) – The Classic of Tea (Chájīng 茶經) – a treatise written by Lu Yu. It provides a rich account of how tea was cultivated and consumed at the time, including a detailed description of 24 utensils necessary for its ceremonial preparation. That number will sound less surprising once we realise that the widespread form of tea at the time was dancha – leaves compressed into bricks using moulds – which had to be carefully ground and whisked with hot water right before serving. In fact, the custom of brewing whole tea leaves did not emerge until much later during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644). Dancha was even sometimes used as currency, and it is most likely in this form that tea first came to Japan.

The seeds of camellia sinensis are said to have been introduced on Japanese soil in 1191 by Eisai, a Zen monk trained in China. From the beginning, tea has been closely linked to Buddhist monastic communities, for it helped the monks to stay awake during long hours of study and meditation, and the process of its ceremonial preparation allowed them to calm and clear their minds.

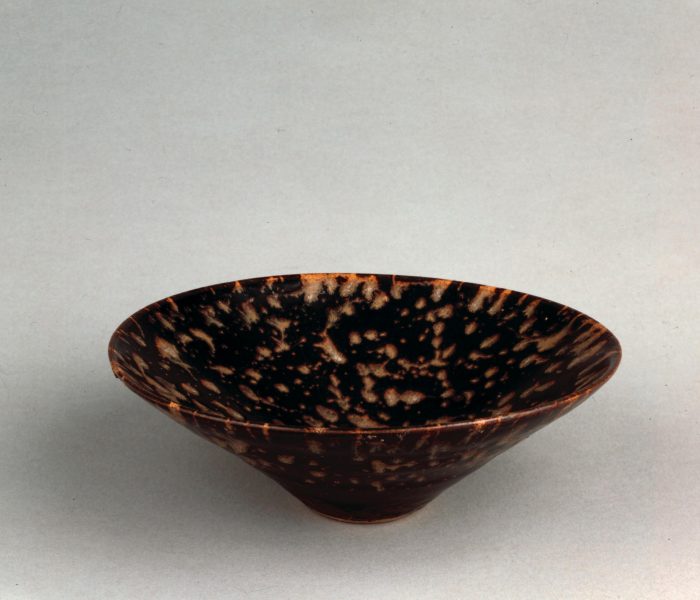

But the practice of tea ceremony spread well beyond the monastery walls. Along with poetry writing, tea drinking became a refined pastime for the lay elites. Intimate tea gatherings allowed people to meet and talk confidentially on equal terms, serving not only as entertainment but also political means. In consequence, wares used for preparing and drinking tea, although primarily utilitarian, became elevated to the status of art pieces collected and treasured by connoisseurs.

Along with the customs surrounding tea that travelled from China to Japan, expensive utensils made by some of the most famous kilns in China were also highly sought after by Japanese elites and passed down from generation to generation. A major change, or “Japanization” of the tea ceremony was brought about by Sen no Rikyū (1522-1591) – the tea master of warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In accordance with the philosophy of wabi sabi, advocated by master Rikyū, fancy Chinese utensils were replaced by simple, frugal ceramics, made locally in kilns such as Bizen, Shigaraki and Mino known for producing utilitarian peasant wares. Serving a purely utilitarian function, these wares were shaped by hand. Along with the impurities present in the clay and the formation of natural ash glazes during the firing process, it yielded one-of-a-kind, perfectly imperfect vessels, whose spontaneous spirit and rustic beauty began to be appreciated by tea connoisseurs.

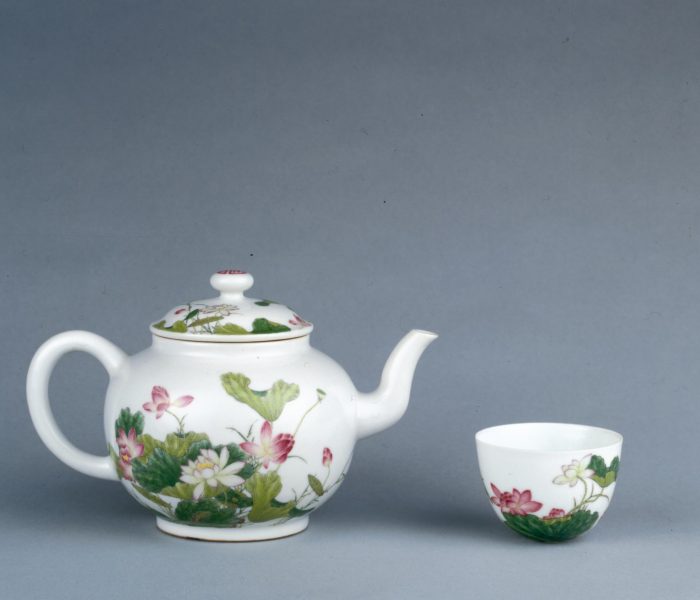

Until this day, tea and tea ceremony play an important cultural role in both China and Japan. Not surprisingly, many kilns and makers once renowned for producing excellent teawares, such as Yixing in China or the Raku family in Japan, continue the ancient traditions to provide new generations of tea aficionados with beautiful ceramics catering to both eyes and soul. While the world around us has changed dramatically and is more fast-paced than ever before, the tea ceremony offers a much-welcome moment of stillness and mindfulness. Perhaps that is why even today so many are still inclined to follow the ancient way of tea (chadō 茶道).