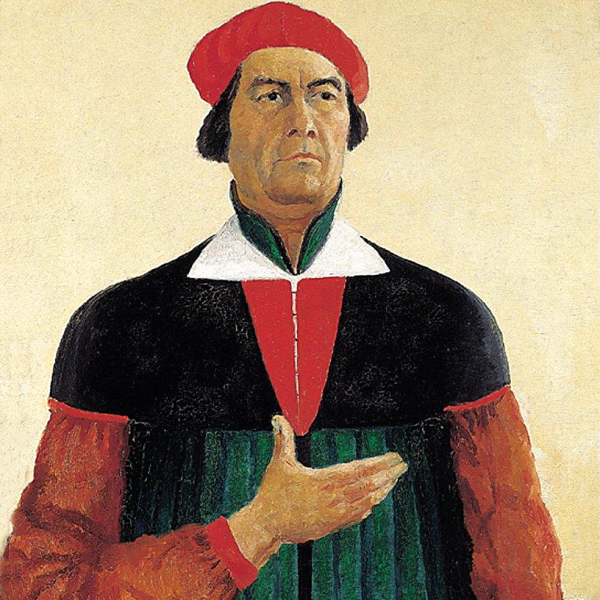

modern icon

It’s safe to say everyone has had a time when they were looking at a work of art and wondered what it was about. If you’re one of those people, know that you are not alone. Even for our editorial team here at Artbuk, despite our background in the history of art and contact with many surprising pictures over our five-year studies, there are to this day some works that can leave us speechless. It has also happened that we were visiting a museum and didn’t know if what we just saw was an exhibit or simply something that someone had left behind.

Contemporary art is famous for requiring almost map-like guidance in order to be able to understand what it tries to convey. Without it, one is most likely to either get lost amidst the multitude of random associations, or jump to the hasty conclusion that the artist simply couldn’t paint realistically, hence this whole flair for abstraction. And well, this just isn’t the case.

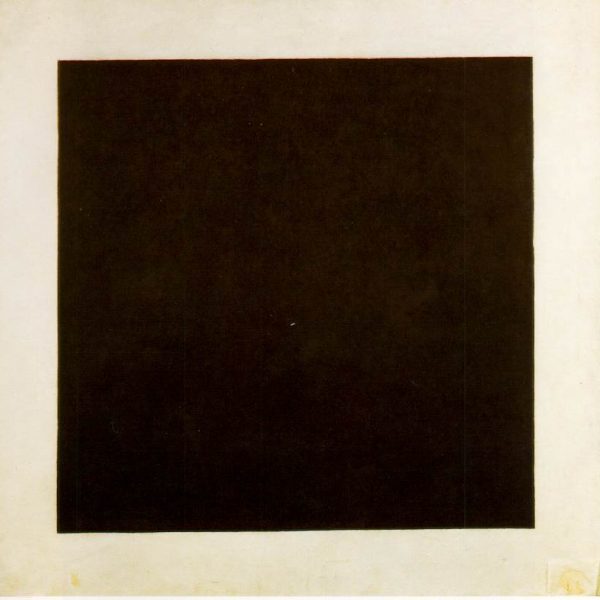

Today we are taking a closer look at one of the most famous from among such works, namely Black Square by Kazimir Malevich, a painting much more difficult to grasp than it may appear. We will try to walk you through it step by step.

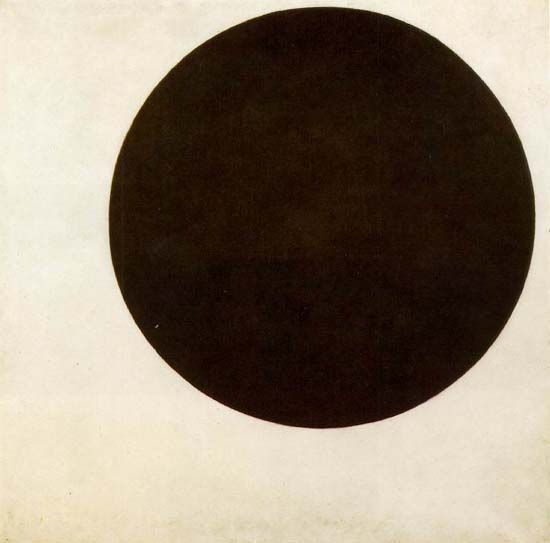

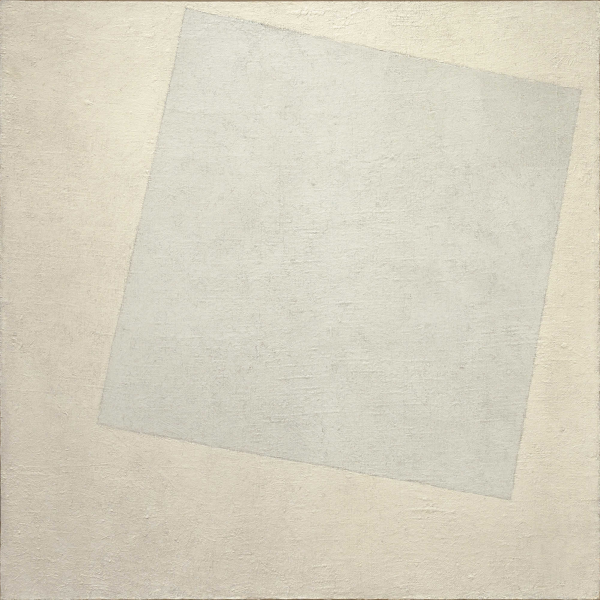

To begin with, it is an abstract composition belonging to suprematism – an avant-garde art movement created in 1915 by Malevich himself. What was it about? Put simply, about departing from art that showed reality as it was. By adopting suprematism, Malevich turned his back on portraits, landscapes and still lifes. More important than what the work presents was to be how it makes the viewer feel. According to Malevich, limiting art to the most simple geometric figures, the so-called painting atoms, such as squares, was supposed to simplify art by removing the aspects of objectivity and literality.

This is, however, where the main problem lies, because for many, this kind of simplification is not a simplification at all – quite the contrary. Learning the assumptions of a theory versus feeling and understanding it in real life are two very different things! When we look at a landscape, we can experience amazement. When we look at a portrait, we can admire the model’s beauty. But what are we supposed to do with a black square on a white background? Exactly – it’s hard to say.

On the other hand, this ignorance creates a space in which certain associations or emotions can sprout. Malevich stressed that art so far had always served something, be it religion, state or a certain ideology. The idea behind suprematism was to show art at its purest, where the tool to properly experience it was none other than our own intuition. Malevich believed that it was precisely intuition – and not intellect or knowledge – that was necessary not only to understand art, but also the place of man in the universe.

The square as a geometric figure was for Malevich “a sign of man’s victory over the chaos of nature”, and therefore a symbolic representation of law and order. The comparison that the artist used was that of a religious work of art, where the black square was supposed to be a modern icon that would refer us to higher, spiritual values and sensations through minimalist means, so fitting with those new times.

Today, shocking and surprising art is nothing new, but for many at that time, both the painting and the comparison were iconoclastic and unacceptable. Back in 1915, when it was painted, Black Square was a truly revolutionary feat that paved the way for abstract art and help break away with the artistic achievements of all previous generations. That’s why it is considered to be one of the most important works of art in history, even if we still think of it as merely a black square on a white background.

transl. Jakub Majchrzak