to be, or not to be?

There is a lot of talk in the Polish media about the reconstruction of the Saxon Palace, the Brühl Palace and tenement houses located on Królewska Street in Warsaw. The bill has just been presented to Polish Parliament, and the investor of the project estimated at nearly PLN 2.5 billion is the Treasury. Meanwhile in Israel, refurbishment works are being carried out on a monumental temple, the ruins of which have been buried underground since 363 A.C..

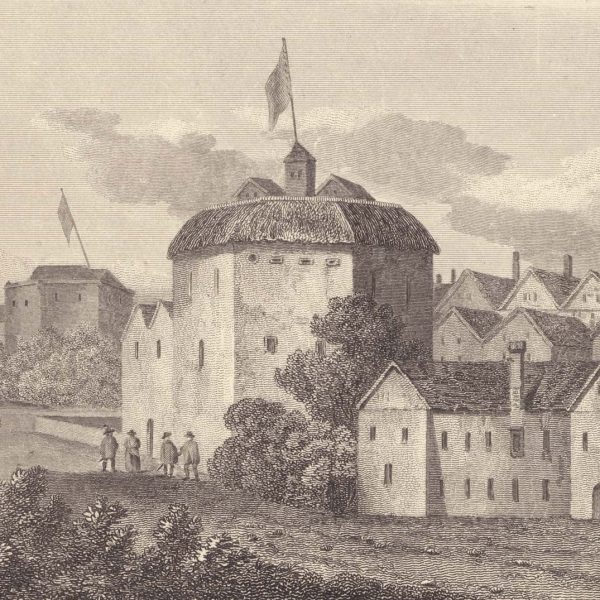

None of these projects can be denied ambition or grandiosity. As a society, however, we should ask ourselves a very important question about the appropriateness and necessity of such decisions. War dramas, natural disasters, structural defects, city revamps or even terrorist attacks – history seems to have little pity for the landmarks around the world that have been either damaged or destroyed for a variety of reasons. Some have been rebuilt and these are obviously must-see monuments! The question is, at what point does a monument cease to be a monument?

To paraphrase the famous quote: to rebuild or not to rebuild, that is the question. Among conservators, the issue of authenticity (material, workmanship, history) is a controversial topic that has been dividing people for almost two centuries. Think of it as a football match, where team A are purists – supporters of refurbishing and clearing objects of historical add-ons to make the building a faithful representation of a particular style even if no sources on which to rely have been preserved. Here, the captain’s armband would be proudly worn by the 19th-century French architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc. Team B, meanwhile, are the opponent led by English writer John Ruskin. As an nineteenth-century art critic, he explored the subject of authenticity and compared monuments to a living organism that is born, reaches full bloom, but perishes at some point – that is the natural order of things. Therefore, if there’s a place to seek truth, it must be in the ruins – testaments of the passing time and individual history. What easily comes to mind is the sight of English monasteries whose single walls are surrounded but nothing by a green lawn.

The Far East conservation concept, on the other hand, plays in another league completely. Japan is famous for its beautifully decorated wooden temples and pagodas. However, few people seem to know that, in the Japanese tradition, in order to preserve monuments for posterity, these objects have for many centuries been dismantled every 20 years and rebuilt using new materials. To better understand this practice, it is necessary to refer to culture and faith. The dominant religion in the Land of the Rising Sun is Shintoism, which is why the vast majority of Japanese temples are dedicated to Shinto deities. For Shintoists, matter is of secondary importance and they place a much bigger emphasis on immaterial values . Add to this their harmonious relationship with nature and it is no surprise that wood is the preferred building material. Regular demolitions are intended to preserve the functions and traditions associated with the place of worship.

So let’s go back to the question: to rebuild or not to rebuild. And if so, is it supposed to be a faithful copy or maybe a facelift commemorating the damaged prototype? The answer to that will probably never be clear.

transl. Jakub Majchrzak